“Everywhere, where right and glory lead.”

Motto of the Royal Engineers

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that the closer you live to something, the longer it takes you to get round to visiting it.

I have lived in Gillingham, home of the Royal Engineers Museum, for 17 years.

I finally managed to get round to visiting it in April 2024, an embarrassing 16 years after I first arrived.

Last year, I stumbled across a social media post about ‘Build, Demolish, Defuse’ weekend at the Royal Engineers Museum. I’d never heard of this event before, but it sounded interesting, so The Man of Kent and I decided to pop down and see what it was all about. It was a glorious day weather-wise, so we walked there via the Great Lines.

“What the hell was that?!” I exclaimed in a ladylike manner as we reached the bottom of the Great Lines Heritage Park. We had just heard a shot so loud it sounded like it was right in front of us. Another shot rang out shortly after. It couldn’t be coming from the Royal Engineers Museum, surely?

As it turned out, yes, it could. We arrived at the museum just in time to see a soldier firing a musket like they do in Sharpe. The gun sounded loud on the Great Lines, but up close the noise was deafening; my ears were ringing. Brilliant to see one being fired in real life though.

What we hadn’t appreciated then, is that the Royal Engineers Museum is VAST. We had decided to toddle down for the afternoon, but soon realised that was a major tactical error – there’s so much to see! And so much to do on Build, Demolish, Defuse weekend. One afternoon was not going to be enough time. Seriously poor planning and reconnaissance on our part.

This time, with the benefit of recon and intel from last year, we came better prepared and armed with a plan of attack. Today’s blog is a debriefing of our trip.

About the Royal Engineers Museum

The Royal Engineers Museum is Kent’s largest military museum. It has over 1 million items relating to the history of the Royal Engineers and military engineering. Among them are Wellington’s map from the Battle of Waterloo and a piece of the Berlin Wall (more on that later). Architecturally speaking, it’s beautiful. The Ravelin Building, home of the main museum collection, used to be the Corp’s Electrical School. It was designed by Major E.C.S Moore, himself a Royal Engineer.

The Royal Engineers Museum is tremendous value for money. At time of writing, tickets are £17.50 and valid for a whole year! That includes access to all the various events that are on throughout the year. Given that you need about a week to see all the cool stuff here, having a year-long ticket is ideal. You can go back as many times as you like, instead of trying to cram everything into one visit, thus avoiding the dreaded museum fatigue.

Even better, if you live somewhere that has a Medway postcode, you get a discount on your ticket. Annual tickets for local adults are £15.00 at time of writing.

What is a Royal Engineer?

The Royal Engineers are the armed forces’ builders and demolition experts. You can’t wage a successful war if you can’t get across enemy territory, and you can’t get across enemy territory if you don’t know where you’re going, or if there are obstacles in the way. The Royal Engineers are the people who will get you from A to B, bridging, defusing and clearing any obstacles along the way.

Royal Engineers are often known as ‘sappers’. This comes from the French word sappe, which means ‘spade’. It’s a nod to the Engineers’ historical expertise in tunnelling and digging trenches (‘saps’ en français). Royal Engineers are also experts in reconnaissance, mapping and surveying. Wellington would not have won the Battle of Waterloo without the maps drawn up by the Royal Engineers, and their expertise was the foundation of modern Ordnance Survey maps.

The Royal Engineers have been on the frontline of every major and minor conflict of the British Army, and have won 55 Victoria Crosses for their bravery. They can trace their origins all the way back to Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester. Gundulf built Rochester Castle, Rochester Cathedral and many other buildings around Kent, and is regarded as the first ‘King’s Engineer’. The Engineers’ links to Gundulf are reflected in the memorials to the regiment in Rochester Cathedral.

Build, Demolish, Defuse weekend

The annual Build, Demolish, Defuse event is not to be missed. It’s exciting, informative, entertaining and noisy.

A good soldier can fire three rounds a minute

One of the most exciting parts of Build, Demolish, Defuse weekend is the live demonstration of weapons. This year, we saw three.

If you’ve ever watched the TV series, Sharpe, you’ll know that a good soldier can fire three rounds a minute, in any weather. In Sharpe’s Eagles, Sharpe says to his troops, “All you’ve got to do is stand, and fire three rounds a minute. Now, you and I know you can fire three rounds a minute. But can you stand?”

It is not easy to stand and take a steady photo when someone is firing a machine gun in front of you, let me tell you!

First up, a Napoleonic sapper demonstrating a Brown Bess Flintlock musket. This sleek weapon has given us several famous phrases in the English language. For example, ‘flash in the pan’. This has nothing to do with cooking. It’s the name for what happened when the gunpowder ignited in the firing pan of the musket (creating a flash) but failed to set off the main firing charge. So a flash in the pan looked good, but didn’t actually do anything.

Flintlocks are also the origin of the phrase ‘half-cocked’. Having the gun ‘half-cocked’ was a safety measure because it would prevent it from firing. This led to the British expression ‘going off half-cocked’, meaning to be unprepared or not fully ready for something.

The Brown Bess musket is impressive to look at, and thunderously loud when fired.

You could tell which members of the audience had been to Build, Demolish, Defuse before; they were the people who shuffled ten paces backwards before any shots were fired. Everyone else jumped a foot into the air and covered their ears (much like I did during my first musket demo last year).

But how were Flintlock muskets used effectively against the enemy? Well, soldiers would line up, shoulder to shoulder, creating a ‘thin red line’ of fire. They would stand so close together that heat, smoke and powder blowback from the guns could result in burns to the face, hence the origin of the term ‘sideburns’.

Drummer boys were essential to the success of the thin red line, because they would beat out the count for the soldiers to follow when firing. Unfortunately, this meant that the enemy would usually aim to shoot the poor drummer boys first, because without the drums, the soldiers wouldn’t know when to fire.

From 3 rounds a minute to 500 rounds a minute

The second demonstration was a short magazine Lee Enfield bolt action rifle (‘SMLE’). This was the standard service rifle of the British Armed Forces until the 1950s. It’s magazine-fed, so much faster to fire compared to the Brown Bess musket we saw earlier. Never mind three rounds a minute, the SMLE could do rapid fire – 20 to 30 rounds in just 60 seconds. It was so quick to fire in fact, that there are WW1 accounts of German soldiers reporting they had been facing machine gun fire, when actually they were up against British soldiers with SMLEs.

The final demonstration was a Vickers-Maxim machine gun. This was adopted as the standard machine gun for the British Armed Forces in 1912. It was heavy, and cumbersome; it needed several men to move, set up and operate it. However, once in position, it was a solid, reliable and formidable weapon, able to fire 450 to 500 rounds a minute.

Guns, swords and medals – the Armoury tour

Next on the plan of attack was a tour of the Museum’s armoury.

We had visited the enormous armoury of the Grand Master’s Palace in Valletta a few weeks’ earlier. In comparison, the Royal Engineers’ Armoury felt cosy and snug, but no less interesting. About the size of our living room, it’s filled with guns, ranged weapons, edged weapons and hand weapons of all eras. The Museum also looks after several Victoria Crosses belonging to former Royal Engineers.

The Victoria Cross is the most prestigious decoration that can be given to members of the British Armed Forces. It is awarded “for most conspicuous bravery, or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy.”

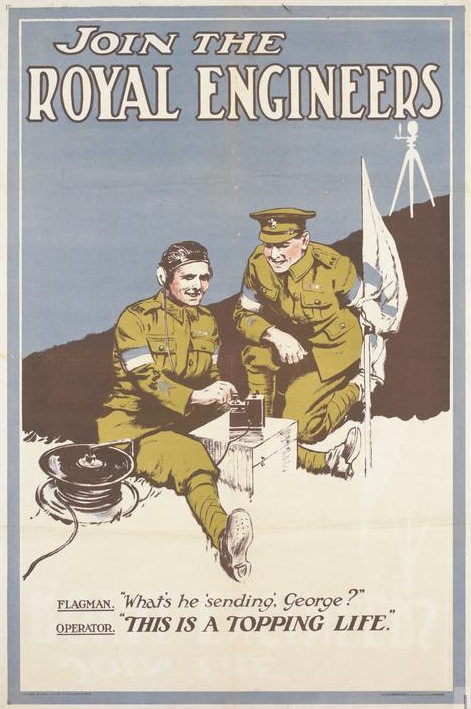

© IWM, Original source.

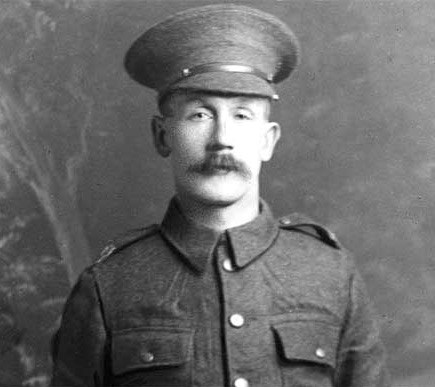

Sapper William Hackett was one of the Royal Engineers awarded a Victoria Cross. He showed selfless bravery while trying to rescue fellow tunnellers who had been trapped in a mine explosion near Givenchy in France. His citation in the London Gazette reads:

“For most conspicuous bravery when entombed with four others in a gallery owing to the explosion of an enemy mine. After working for 20 hours, a hole was made through fallen earth and broken timber, and the outside party was met. Sapper Hackett helped three of the men through the hole and could easily have followed, but refused to leave the fourth, who had been seriously injured, saying,” I am a tunneller, I must look after the others first.” Meantime, the hole was getting smaller, yet he still refused to leave his injured comrade. Finally, the gallery collapsed, and though the rescue party worked desperately for four days the attempt to reach the two men failed. Sapper Hackett, well knowing the nature of sliding earth, the chances against him, deliberately gave his life for his comrade.”

We also saw the Victoria Cross given to Sergeant Thomas Durrant, a Royal Engineer from Faversham in Kent. Durrant was manning a Lewis Gun on board HM Motor Launch 306 during the St Nazaire Raid in 1942. Despite being shot several times while the Launch was under heavy enemy fire from a German destroyer, he refused to leave his post until the destroyer came alongside and took those still alive prisoner.

Durrant’s Victoria Cross is unique because it is the only one to have been given during a naval action, and unusual because its award was suggested by the German commander who was in charge of the destroyer.

Another Royal Engineer from Faversham who won a Victoria Cross was Lieutenant General Sir Philip Neame. Neame was also part of Great Britain’s Running Deer team at the 1924 Olympics, making him the only Victoria Cross recipient who has won an Olympic gold medal. His medal is at the Imperial War Museum.

We were able to handle several weapons during the tour. I discovered that old rifles are extremely heavy compared to their modern equivalents. You know you’re having an unusual afternoon when you’re holding an AK-47, appreciating how light and comfortable it is compared to a Boer War rifle! Although as The Man of Kent said, “She who would prefer an AK-47 probably shouldn’t be given an AK-47.” Wise words.

Tanks, mines and bridging, with Lt Col ‘Sticky’ Whitchurch

Now, I have written before about how The Man of Kent and I love a guided tour and/or expert talk on a subject. Well, we were completely spoiled at Build, Demolish, Defuse because we got to enjoy three brilliant talks by Lieutenant Colonel (R) Matthew ‘Sticky’ Whitchurch.

This was not military tactics for dummies. Lt Col Whitchurch’s talks were like proper military briefings, and all the more enjoyable for it. We got pacey, hugely informative crash-courses on tanks, mines and military bridging, covering topics you’ve probably never had to think about as a civilian (unless you play games like Risk or Civilization). Each talk had something for everyone – beginners, enthusiasts and experts alike – and were an engaging combination of history, video, and plenty of practical how-to.

If you came in knowing nothing about tanks, mines or bridging (like I did), you left these talks knowing a LOT more. To prove I was listening, here’s a quick run-down of what we learnt.

Tanks, and the importance of tea

Lt Col Whitchurch’s first talk was on Armoured Engineers and the many ways that tanks can be deployed; bridging gaps, clearing mines, providing covering fire and clearing routes for infantry.

We learned about how Royal Engineers were trailblazers in the development of the modern tank. Major General Sir Percy Hobart developed modifications for tanks so that they could overcome obstacles, such as walkways that could bridge gaps. These modifications became known as ‘Hobart’s Funnies’ and played a key role on D-Day. The (magnificently named) Sir Giffard Le Quesne Martel was instrumental in the development of tanks for bridging, and pioneered the idea of the Martel Bridge.

We also learned about the evolution of tank design, capability and functionality, from the original Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE) through to modern Centurion tanks.

My favourite tank fact? From the end of World War II, Centurion tanks were fitted with a ‘boiling vessel’ so that soldiers could make tea! No more having to stop and get out for a drink; instead, you could have a brew from the comfort of your own tank while deploying a bridge or blowing up the enemy. Pioneering tea on board tanks – makes you proud to be British!

Mind the mines!

Having enjoyed Lt Col Whitchurch’s first talk so much, there was no way we were missing the others.

If further proof was needed of how fascinating the Armoured Engineers talk was, it is this: The Man of Kent, who is fuelled by coffee, happily skipped a mid-morning coffee break to go straight from the Armoury Tour to Lt Col Whitchurch’s next talk, ‘Achtung Minen!’

This was a fascinating briefing about the different kinds of mines and obstacles. Tactical vs nuisance, natural vs artificial, bar mines, scatter mines, challenges and ethical considerations (for example, clearing up mines after a conflict). Fascinating, but grimly topical given current events in Ukraine and on European borders.

No bridge? No problem!

The final talk of the day was about military bridging. Bridging tanks are amazing! Check these out:

No bridge? No problem with one of these babies!

Navigating obstacles is a military challenge as old as time. But thanks to Hobart’s Funnies and other developments, modern tanks can be adapted to lay bridges, cross ditches and craters, and plug gaps that would otherwise be impassable for vehicles and infantry. The scale of these tanks is quite incredible – they tower over you when you stand next to them in the museum grounds.

Temporary, movable bridging is handy, but fixed bridges are just as important for keeping transport and supply lines open. The Royal Engineers’ expertise has been vital for designing, building and maintaining fixed bridges – notably railway bridges – all around the world.

It was an honour and a privilege to have had not one, but three talks from Lt Col Whitchurch, plus a guided tour of the ‘metalwork’ (tanks, to us civilians) in the museum grounds. I now feel thoroughly prepared should I need to engage the enemy in Gillingham. I just need to get myself one of those lovely Centurion tanks with a tea vessel first…

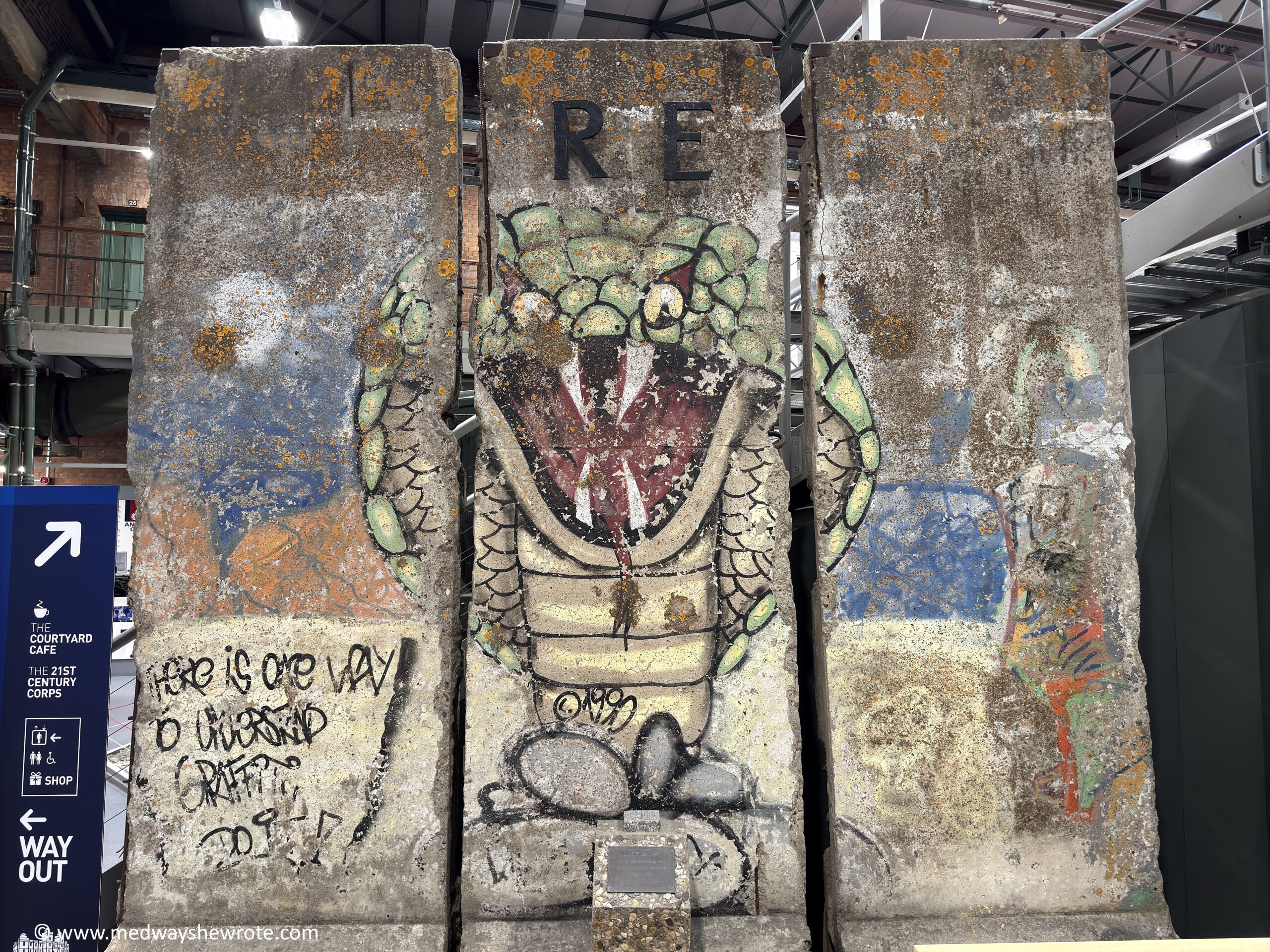

The Berlin Wall in Medway

Did you know that part of the Berlin Wall is in Gillingham? I didn’t!

We had been refuelling at the mezzanine coffee shop in the Museum’s main hall. This is a coffee shop with a view. A place where you can have your tea overlooking a German V2 rocket, military planes – and an actual chunk of the Berlin Wall.

When The Man of Kent pointed this out, I thought it must be a replica. It couldn’t possibly be a real bit of the Berlin Wall, because why would a piece of this world-famous historical monument be in Medway, of all places?

Astonishingly, it is the real thing! But how did this whopping great slab of the Berlin Wall end up in Gillingham?

Let me tell you. When the Second World War ended, seven units of Royal Engineers were stationed in Berlin to help restore utilities, and build hospitals and accommodation. In 1957, these seven units were combined into the Berlin Field Squadron, which played an important role in developing defensive plans for the city.

After the Berlin Wall came down on 9 November 1989, Berlin Field Squadron was involved in dismantling a section of the Wall at Staaken Checkpoint, in West Berlin. This section of the Wall now stands inside the Royal Engineers Museum. A great example of how international the work of the Royal Engineers was, and still is.

It’s coming home; The Royal Engineers and the FA Cup

Here’s a fact to remember for pub quiz fans; 150 years ago, in 1875, the Royal Engineers won the FA Cup! They played against the Old Etonians at the Oval on 13 March 1875. That match was a 1-1 draw, resulting in the first-ever FA Cup replay, which the Engineers won 2-0. This excellent piece by Col A Philips gives a full match report if you’d like more details about the game.

I knew the Royal Engineers Museum had a replica FA Cup. Being married to a football fan, this was one object I had to track down on my visit.

The replica FA Cup and the original match report are on display at the Museum until August 2025. Meanwhile, to commemorate the win, the Royal Engineers and Old Etonians staged a ‘replay’ of the 1875 game at King’s Bastion barracks in May.

And finally

If you haven’t been to the Royal Engineers’ Museum yet, get down there on the double for a great day out. You don’t need to wait for Build, Demolish, Defuse weekend, there’s plenty to see on any day of the year. Definitely do not wait 17 years to visit like I did. I’m going to be making the most of my annual ticket and having a few leisurely strolls around the rest of the exhibitions. I need to find out more about the Museum’s mascot, Snob the Dog, for one thing…

Have you been to Build, Demolish, Defuse? Have you got a favourite item in the Royal Engineers Museum you think I should see? Can you fire three rounds a minute? Tell me in the comments.

Leave a Reply