Me: “Do you think there were food stalls selling burgers and hotdogs, like on Bonfire Night?”

The Man of Kent: “More like peanuts and pies, beer and gin. Can’t imagine people were watching the execution sober.”

New Year’s Day 2026. The Man of Kent and I were walking on the Great Lines, and I was telling him the story of how Benjamin Gardiner had been executed here for murdering Sergeant Patrick Feeney, in 1834.

I was pondering what the scene must have looked like, almost two hundred years ago, when around 14,000 people packed onto the Lines to see one man put to death. I started thinking about the annual fireworks display that, until recently, happened most years on the Great Lines. As anyone who has attended that display knows, you can cram hordes of people onto those hills and fields. On Bonfire Night, there would also be food trucks catering to the spectators.

That’s when it occurred to me. With so people around to watch the execution, there were bound to be vendors who wouldn’t miss the opportunity to turn a handsome profit. Hence my question to The Man of Kent. I wasn’t being flippant; just voicing a morbid thought.

As it turns out, The Man of Kent wasn’t far off. Executions had entertainment value in those days, and local food and drink sellers would indeed ply their wares to the crowds. In fact, one former pie seller would play a prominent and sinister role in this particular affair.

Today on Medway, She Wrote: the murder of Sergeant Patrick Feeney at Chatham Barracks, the execution of Private Benjamin Gardiner on the Great Lines, and the portfolio career of Britain’s busiest hangman, William Calcraft.

A summer evening discovery

A year or so ago, The Man of Kent and I were heading to Chatham Intra for a night out. It being a fine July evening, we decided to stroll there via the Great Lines, a favourite walk of ours.

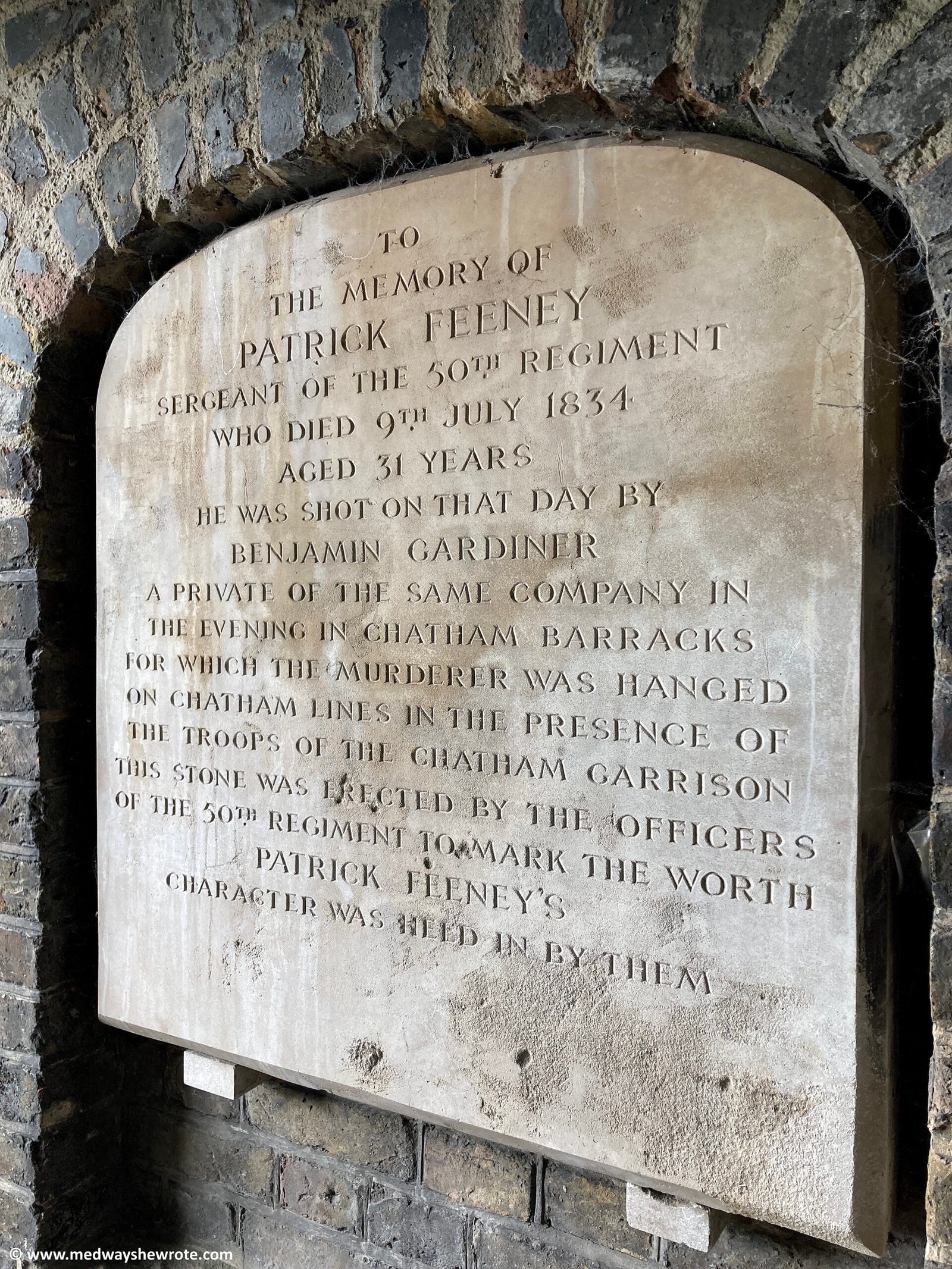

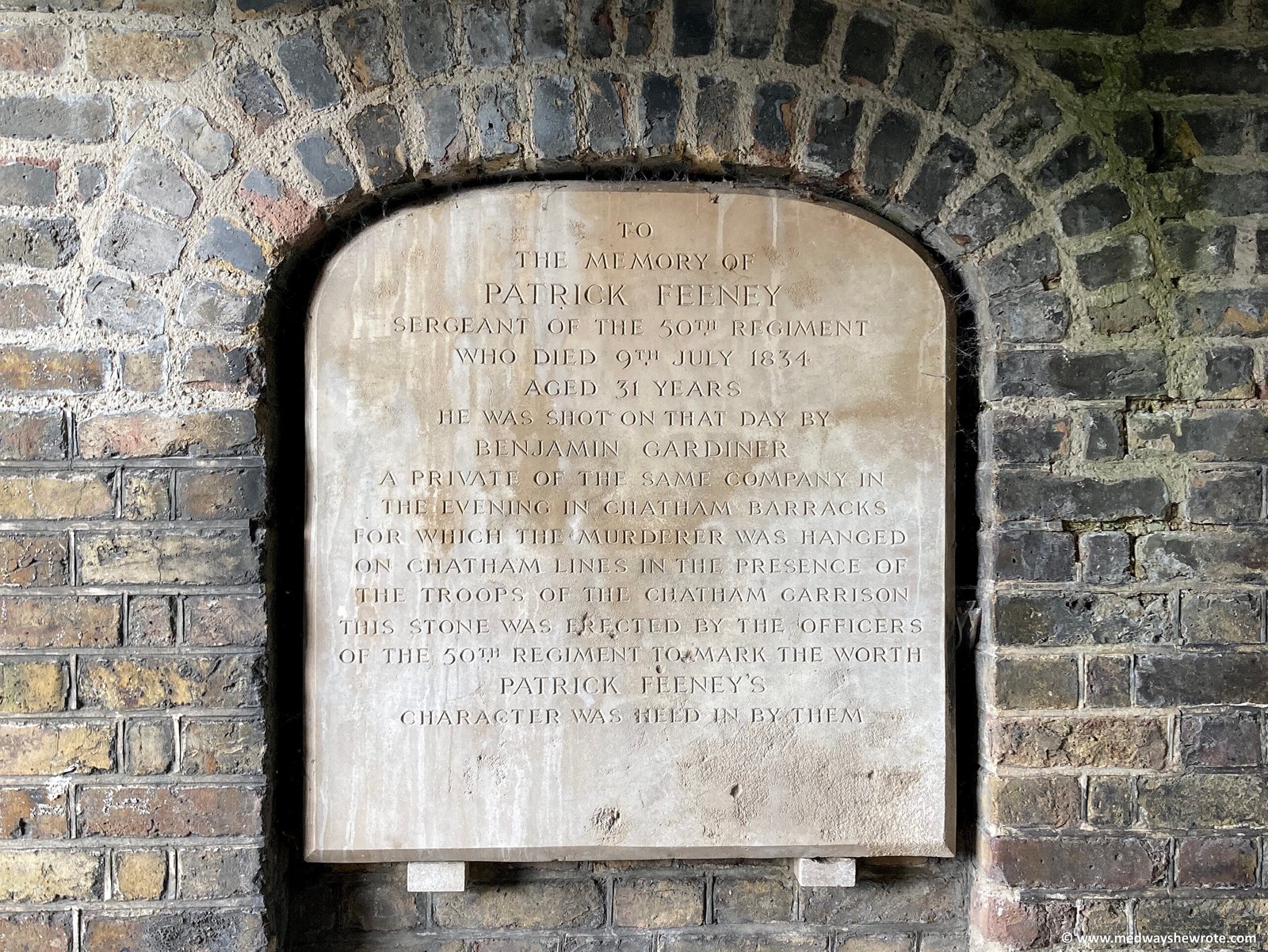

We reached Town Hall Gardens at the bottom of the Lines. Normally we would plough straight across, following a stony, tree-rooty path trodden into the ground by years of feet too lazy to use the proper route through the entrance gate. That day, however, I was wearing flimsy summer shoes, so for once – possibly for the first time ever – I insisted on following the paved path. That’s how I discovered the memorial plaque to Patrick Feeney, just inside the entrance gate. It reads:

TO

THE MEMORY OF

PATRICK FEENEY

SERGEANT OF THE 5OTH REGIMENT

WHO DIED 9TH JULY 1834

AGED 31 YEARS

HE WAS SHOT ON THAT DAY BY

BENJAMIN GARDINER

A PRIVATE OF THE SAME COMPANY IN

THE EVENING IN CHATHAM BARRACKS

FOR WHICH THE MURDERER WAS HANGED

ON CHATHAM LINES IN THE PRESENCE OF

THE TROOPS OF THE CHATHAM GARRISON

THIS STONE WAS ERECTED BY THE OFFICERS

OF THE 50TH REGIMENT TO MARK THE WORTH

PATRICK FEENEY’S

CHARACTER WAS HELD IN BY THEM

Well, I couldn’t leave that unresearched. What I learned is a story of a shocking murder at a military barracks, the swift trial and execution of the man who committed the crime, and many gory details about hanging in the 19th century. Read on for more.

The murder of Sergeant Patrick Feeney

The facts are briefly these.

On 9 July 1834, Sergeant Patrick Feeney was inspecting the troops on parade at Chatham Barracks. Private Benjamin Gardiner was among the troops and, by all accounts, visibly drunk. Noticing this, Sergeant Feeney ordered a corporal to take Gardiner to the guard room. In response, Gardiner fired his musket at Feeney at point-blank range, mortally wounding him. As he was taken into custody, Gardiner exclaimed, “I have rid the world of a rascal and tyrant!” and, “If he is not yet dead, I hope he soon will die, for I am not afraid of the rope.”

Gardiner’s shot passed through Feeney’s body and broke two ribs. Though treated by the assistant surgeon at the barracks, Thomas Campbell, Feeney died two hours later. Gardiner was handed over to the local police, and the case against him began.

The trial of Benjamin Gardiner

Justice moved swiftly in those days.

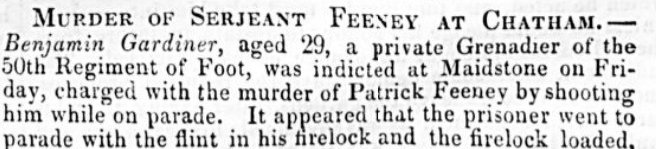

The inquest was carried out the next day at the Mitre Tavern (now demolished, I believe), with Robert Hinde, the local coroner, presiding. Gardiner’s trial took place a week later at Maidstone Assizes.

At the trial, Sergeant George Hewer of the regiment gave evidence about the incident. Gardiner had appeared to be staggering in the ranks. Feeney had given the order for him to advance two paces and stand “right about face.” Gardiner obeyed, but staggered in doing so. Feeney then gave the order “left about face.” Gardiner again staggered and it was “obvious that he was in liquor” i.e. drunk. Feeney called Corporal Donlevy and asked him to take Gardiner to the guard room, at which point Gardiner fired his musket, fatally shooting Feeney. Two corporals from the regiment gave similar evidence.

By all accounts, Gardiner’s musket was loaded contrary to orders. Evidence was given that muskets were never loaded for parade, and not loaded generally unless a soldier was on convict guard.

The Kentish Gazette reported Sergeant Hewer telling the court that, when they reached the guard room, Gardiner had turned to him and said, “Sergeant Hewer you are safe, for you are living; but that musket has been laden for you before.” Was this a cold statement of murderous intent, or the ravings of someone off his head with drink? Either way, pretty incriminating.

Gardiner only made the following written statement in his defence:

“I beg humbly to state to your Lordship that I did not know the gun was laden. I was in a state of intoxication when the piece went off, and did not know what I said or did. I owed the deceased no animosity, and I deeply deplore having been the cause of the accident, and therefore throw myself on the mercy of the court.”

It was up to the jury to decide whether or not Gardiner’s musket had gone off accidentally. The jury didn’t think much of Gardiner’s defence, taking less than five minutes to declare him guilty of ‘wilful murder.’ I don’t blame them. Gardiner saying he owed Feeney no animosity was rather unconvincing given he’d described him as a “tyrant” who he “hoped would soon die”, whether he was parlatic with drink when he said it or not.

The judge, Mr Justice Littledale, ordered Gardiner’s execution, which was originally scheduled for 28 July 1834. In those days, executions were usually carried out in Maidstone. However, and most unusually, the Commandant of the barracks, Sir Leonard Greenwell, wrote to the Home Secretary asking for this execution to take place in Chatham instead. Gardiner’s execution was put on hold pending the decision.

The reasons for the request to hold the execution on the Lines are unclear. The motivation may have been to make an example of Gardiner and deter anyone from following in his footsteps. One newspaper suggested the move was requested, “with the view…of giving a check to that insubordination which too frequently manifests itself in that great military depot.”

Whatever the reason, the Home Secretary allowed the change of location. Gardiner’s execution was rescheduled for Thursday 31 July, just a few weeks after Feeney’s murder. As I said, justice moved quickly in those days.

The press reports

Proving that not much has changed over the years, the press were quick to report on the murder and start muckraking details about Gardiner’s life.

How much of the reporting about Gardiner’s past was based on fact, and how much was colourful embellishment, I can’t say. Nevertheless, according to reports, Gardiner was from an Oxfordshire family who occupied “a humble station in life.” Physically, he was “a tall, hard-featured man of dark complexion.”

Several newspapers reported that Gardiner was formerly in the Royal Marines but his character was “so notoriously bad that he was drummed out of the corps.” The Essex Standard added to this, stating Gardiner:

“…has been in the 50th Regiment for about two years, but his company was shunned by the generality of his comrades; on account of his dreadfully uncouth manner, and his frequent inebriety, the better disposed soldiers were afraid of being deemed his associate.”

The Maidstone Gazette and Kentish Courier went even further on 5 August, stating, “His general character, from his youth to his execution…had been irregular and depraved.”

By all accounts, a wrong ‘un, then.

The execution of Benjamin Gardiner

The weather was dismal on Thursday 31 July 1834. Despite this, there was a vast crowd – around 14,000 people.

The military presence was substantial. According to one report, “every soldier of every rank and corps connected with the garrison had orders to attend the spectacle, the hustle was most extraordinary.” This included the 50th Regiment of Foot, the 17th Regiment of Foot, the Royal Marines and Marine Artillery – around 2,000 men and their officers in full uniform. “A most imposing effect,” as one newspaper described. Add to that around 12,000 members of the public; quite the turnout.

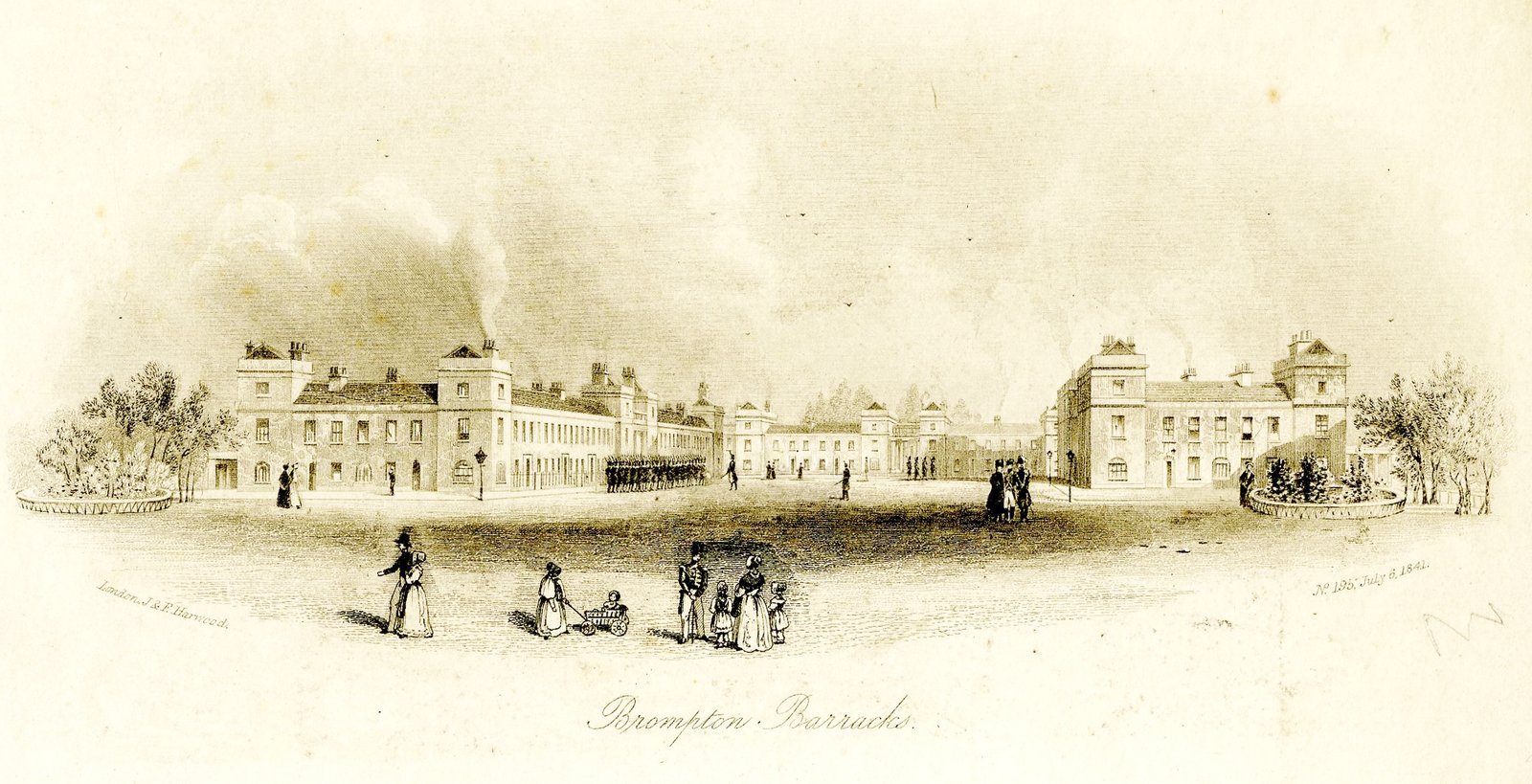

The Maidstone Gazette and Kentish Courier provided a full account of the day itself. According to its article, the gallows stood “on the Mount, at the entrance to the lines from the Sally-port, opposite Mansion Row.” The scaffold had been erected overnight, and was the same one usually used at Maidstone. How grimly handy. The troops were ranged opposite the gallows with Commandant Greenwell at their head.

Gardiner left Maidstone prison around 9:30am and was escorted to the Lines via Chatham High Street, Dock Road and Brompton, accompanied by a bevy of guards, a priest, and the executioner, William Calcraft (more on him in a bit). The route was lined with spectators, many of whom would subsequently make their way to the Lines to watch the execution.

On reaching the Lines, Gardiner received final spiritual consolation from the priest, mounted the platform where the scaffold stood, and gave his last words:

“Gentlemen, I am guilty of the crime for which I am about to suffer, and I’m sorry for it. I beg also to state that unless it had been for drink, I should not have been here today, I dare say.”

At 11:46am, the drop fell and Gardiner was hanged. His body was left suspended on the platform for an hour before being cut down and taken back to Maidstone in a coffin alongside the scaffold. Gardiner was buried in an unmarked grave in Maidstone prison yard. A memorial to Feeney was later commissioned by his fellow soldiers, as we have seen.

The executioner: William Calcraft

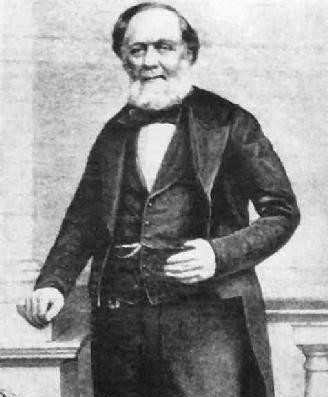

There’s another man with a prominent part in this sorry affair: the executioner, William Calcraft. A man who managed to go from selling pies on hanging days in London, to earning the dubious accolade of carrying out the most executions in British history.

Calcraft was born in Little Baddow, Essex in 1800. He started his working life as a cobbler, with a side hustle as a pie seller. He would hawk pies outside Newgate Prison in London on execution days, and it was while doing this that he got chatting to John Foxton, who was chief executioner at the time. Proving that, as my Mam used to say, it’s not what you know, but who you know, Calcraft’s introduction to Foxton quickly got him a new job – flogging juvenile prisoners for half a crown (around £10 per urchin in today’s money).

Following Foxton’s death in 1829, Calcraft was promoted to head executioner for the City of London and Middlesex. It was a lucrative job. The average fee for a hanging was £2 to £5 per person – around £285 to £700 today. Because hangmen were employed on retainer, essentially acting as private contractors, they could work all over the country, usually negotiating higher fees when they did so (hence why Calcraft could work in Kent). Calcraft made good use of the new railways to travel between jobs. This made him, in the words of his great-great-great-grandson in a BBC interview, one of the first long-distance train commuters.

In addition to their fee, executioners were allowed to keep the clothes and personal belongings of the people they hanged. In Calcraft’s case, assuming he didn’t want the belongings himself, he would sell them to Madame Tussaud’s in London for display in the Chamber of Horrors gallery. Charming. There was a creepy demand for execution merch in those days, with even the rope used to hang the convict being sold for up to £20 at today’s prices. It’s possible this is the origin of the phrase ‘money for old rope’, though that’s a matter of debate.

Calcraft is estimated to have carried out around 450 executions in his career and he racked up several ‘records’ in his time. He performed the last public hanging of a man (Michael Barrett at Newgate, May 1868) and the last public execution of a woman (Frances Kidder at Maidstone in 1868). The youngest person executed by Calcraft was John Anybird Bell, aged just 14, also in Maidstone.

Calcraft was known for using the ‘short drop’ method, which usually meant the person executed took several minutes to die by strangulation. This may or may not have been known to Gardiner, who apparently asked Calcraft to “be quick” as the rope was being placed around his neck. This was not something Calcraft was brilliant at, but no harm in asking, I suppose.

Calcraft would sometimes swing on the legs of the hanging person to speed up death. He was also known to joke with the crowd and was happy to chat to spectators after, occasionally even inviting them to join him in the pub for a drink. All of which has led many to wonder, was Calcraft a sadist, a showman or both?

The crowd of 14,000

Accounts agree that there were around 14,000 people on the Lines to witness Gardiner’s execution. As mentioned earlier, around 2,000 of them were military and around 12,000 members of the public.

No doubt some of the crowd were there because they wanted to see justice served. I am certain that the various regiments present would have borne solemn witness to the execution of the man who had murdered a fellow soldier.

However, research would suggest that at least some of the crowd were there for entertainment purposes. Charles Dickens, Medway’s most famous resident, was vehemently against capital punishment and sickened by the publicity that executions attracted, as well as the attitudes of the spectators. As he wrote to the Daily Times in 1849, “The horrible fascination surrounding the punishment, and everything connected with it, is too strong for resistance.” Interestingly, Dickens witnessed several of Calcraft’s executions.

It was not unusual for people living near places of execution to rent out rooms to people wanting a good view of the proceedings. Food and drink sellers, like William Calcraft in his former career, were guaranteed a decent profit on execution days. The crowds were easy targets for pickpockets and other petty criminals too.

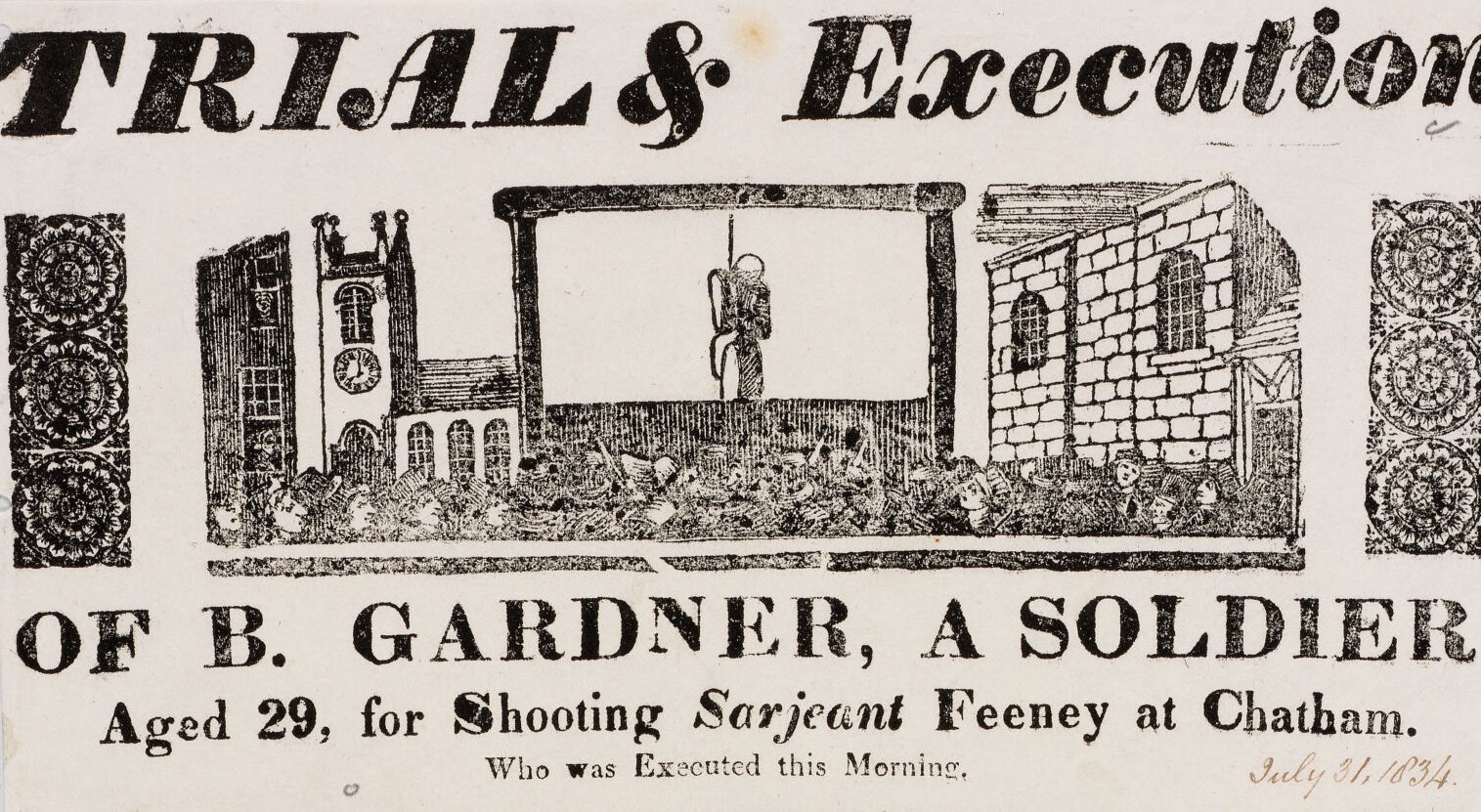

Executions were also a rich source of material for broadsides. Broadsides were large, single-sided, cheaply-printed publications that cost a penny or halfpenny. They were deliberately priced so that most people could afford to buy them (newspapers were expensive at the time because of newspaper tax), and often included woodcut illustrations. Broadsides were intended to be temporary and disposable, and hawked on the street.

Again proving some things never change, the broadsides which recounted what Dickens described as, “revolting details, revived again and again, of bloodshed and murder,” sold best. These reports usually included a description of the crime, an account of the trial and execution, and any last words. Dickens was as contemptuous about broadsides as he was about public executions, writing in one letter to the Times, “We know that last-dying speeches, and Newgate calendars, are the favourite literature of very low intellects.” Oof.

I found an account of Gardiner’s execution in Harvard Law Library’s collection of English Crime and Execution Broadsides. That broadside claims that Gardiner had written a letter to his comrades, exhorting them not to follow his example and to be good soldiers, as follows:

“Dear Comrades…I sincerely hope that after I am dead and gone you will read these lines, it is all poor Gardiner has to leave behind him, and may it be the means of preventing any of my fellow Comrades from falling into the like ungovernable Passions. But may you be good and faithful Soldiers, be obedient and dutiful to your officers, be sober and steady, pay strict attention to their Orders and remember that cleanliness, sobriety and attention is the greatest ornament of a Soldier.”

I can’t find any other reference to this letter, and given that broadsides were known to make up scaffold speeches and confessions (fake news isn’t a modern thing), it’s possible this letter is entirely fictitious.

So, given what we known about the general atmosphere and activities on execution days, I’d say it’s likely that, as The Man of Kent suggested, there were things like pies and peanuts, beer and gin available at Gardiner’s execution, as well as broadsides and other souvenirs afterwards. Ghastly.

History almost repeats itself

In 1865, an eerily similar incident occurred when Major Horatio de Vere of the Royal Engineers was shot during parade by John Currie of the same regiment. In that case, the military authorities were again keen to have the execution carried out on the Lines in full view of the troops, citing Gardiner’s execution as a precedent. However, it was decided not to change the location and Currie was executed in Maidstone.

There was another commonality with Feeney’s murder; Currie’s execution was carried out by William Calcraft.

And finally

A murder of an innocent sergeant, a showpiece execution with a celebrity hangman and a crowd of 14,000 spectators. What a sad and grisly story.

I’ve told you the gory details of Gardiner’s trial and execution. I’ve given you a potted biography of William Calcraft. But there’s one man I haven’t said much about: Sergeant Patrick Feeney.

I can’t give you many facts about Feeney’s life, family or accomplishments. That wasn’t sensationalist enough to make the papers.

What I can tell you, based on available reports, is that Feeney was a well-liked and respected soldier who had only been married a week at the time of his death. He was survived by his wife, his mother who lived at the barracks, and several brothers in the same regiment. Three witnesses at Gardiner’s trial described Feeney as having a “most excellent character in the regiment, particularly for mildness in the performance of his military duties.”

Feeney’s memorial in Town Hall Gardens, erected by his fellow officers, refers to ‘the worth Patrick Feeney’s character was held in’ by his comrades. Further evidence of the esteem in which he was held is the fact that the whole of the regiment, including Commandant Greenwell, attended his funeral.

Thanks for reading! If you’ve enjoyed this piece, you can subscribe to be notified of new posts by email using the link at the bottom of this page. You can also follow Medway, She Wrote on Instagram.

Further reading and listening

- Trial & Execution of B. Gardiner, a soldier (1834) (English Crime and Execution Broadsides, Harvard Library)

- What & Why? The Memorial on the Entry Gate at Chatham Town Hall Gardens by Philip MacDougall (Friends of Medway Archives, Issue 63, August 2021)

- A Hanging on the Lines (medwaylines.com)

- Charles Dickens’ letter to the Editors of The Daily News, 28 February 1846, (Charles Dickens Letters Project)

- Charles Dickens’ letter to The Daily News, 13 March 1946 (Charles Dickens Letters Project)

- Murder & Crime: Medway by Janet Cameron

Newspaper articles used in this piece (available at findmypast.com)

- Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser, 15 July 1834

- ‘Murder of a Serjeant at Chatham Barracks by a Private’, Kentish Gazette, 15 July 1834

- ‘Murder of Serjeant Feeney at Chatham’, Old England, 27 July 1834

- The St James Chronicle and Evening Post, 27 July 1834

- ‘Murder of a Soldier at Chatham’, Kentish Gazette, 29 July 1834

- Caledonian Mercury, 31 July 1834

- ‘Execution of Gardiner the Murderer’, The News, London, 31 July 1834

- The Liverpool Standard, 1 August 1834

- The Essex Standard, 2 August 1834

- Baldwin’s London Weekly Journal and Surrey and Sussex Gazette, 2 August 1834

- Maidstone Gazette and Kentish Courier, 5 August 1834

- ‘Execution of Currie the murderer of Major de Vere’, The Morning Herald,13 October 1865

Podcasts and TV

- The Career of William Calcraft (Consistently Eccentric History, 8 October 2021)

- Holding the Rope: The Victorian History of Hanging (The Devil’s Dinner Hour, 23 June 2024)

- Secret Kent: The killing field at Penenden Heath (21 November 2025)

- Interview with Calcraft’s great-great-great-grandson (Breaking the Seal, BBC, 1996)

Leave a Reply