“Men of Kent and Kentish Men. The natives of Kent are often spoken of in these different terms. Will you be so good as to inform me what is the difference between these most undoubtedly distinctive people?” – B.M.

Notes and Queries, (Vol 5, No. 127), 3 April 1852

I remember the night I first met The Man of Kent. It was at a fancy dress party, first week of university. The theme of the party was ‘P’. One guy came wearing a massive box (‘parcel’). Another came dressed head-to-toe in newspaper (‘paper’), which later proved impractical when they tried to go to the loo. A good friend went all out and came attired in the full armour of a Paladin knight. I had cheaped out on a sparkly tiara from Claire’s Accessories so that I could make a last-minute, lo-fi attempt at ‘princess’. The Man of Kent was dressed as a priest (an unusual choice as he is a staunch atheist).

At some point in the evening, I asked him where he was from. He informed me that he was ‘a man of Kent’. I took this as a purely factual answer. He was describing himself as a man from Kent, in the same way that I might have described myself as a girl from Gateshead. I thought it was a literal description, nothing more.

“I am a Man of Kent” was how he described himself to everyone. He never said, “I’m from Kent” or “I come from Medway.” When someone asked where he was from, he would always proudly announce, “I am a Man of Kent.” If someone queried his rather grand way of stating from whence he came, he would explain further; he was a ‘Man of Kent’ because he came from east of the River Medway. Women from east of the Medway are known as ‘Maids of Kent’. Someone from west of the river Medway, on the other hand, was known as a ‘Kentish Man’ or ‘Kentish Maid’.

The Man of Kent insisted that this distinction was very important. I could understand that. It sounded a bit like the difference between a Geordie and a Mackem. Or a Geordie and a Smoggie. Or any of the other important regional distinctions back home in the North East, where I come from.

Several years later, I married this particular Man of Kent, and we moved into a tiny house in Gillingham, which is east of the Medway. I think that might make me a Maid of Kent by marriage. It definitely makes me a Medway Geordie, anyway.

And that, dear reader, is the story of how I met my husband. It’s also why I refer to him as ‘The Man of Kent’ on this blog.

But how did this distinction between ‘Man of Kent’ and ‘Kentish Man’ come about? I never doubted the Man of Kent’s explanation, but recently I thought I’d look into the history of it myself. What I found were several different theories, a bit of Victorian argy-bargy, and a grand legend that I’d never heard of before – and neither had the Man of Kent himself!

East vs West

Kent has always been divided into East Kent and West Kent. As The Man of Kent first explained to me some years ago, those born in East Kent are generally known as Men of Kent, or Maids of Kent, while people from West Kent are Kentish Men, or Kentish Maids. This is the distinction used by the Association of Men of Kent and Kentish Men.

This division between East and West Kent stretches back centuries. After the Romans cleared out in the 5th century, East Kent was settled by the Jutes and West Kent by the Saxons, so there were some political and ethnic differences between the two parts. In the 600s, East Kent was ruled by King Hlothhere, while Eadric (Hlothhere’s nephew) was King of West Kent. Religion-wise, the county has always had two dioceses – that of Rochester, and that of Canterbury.

The separate kingdoms of Kent lasted for many years, even though relations did seem to get a bit Game of Thrones at times. However, there is no evidence that this historical political divide is the reason we say Men of Kent are from East Kent and Kentish Men from the West. In fact, the boundary seems to have been more administrative than anything else. Although Kent had two different Kings in the 600s, there was just one legal code that covered both kingdoms, and several Royal Charters refer to the ‘Kings of Kent’ – which makes it sound like being a King of Kent was a sort of job share.

From medieval times onwards, words including ‘Kenteys’, ‘Kenters’, ‘men of Kent’ and ‘Kentishmen’ started appearing in the English language, but they weren’t used consistently to describe people from any particular part of Kent. Instead, they were generally used to describe people from Kent as a whole.

Another geography-related theory is that the distinction comes from the location of a small village called Rainham Mark, where there used to be a boundary stone that marked the dividing line between East and West Kent. But again, there’s no evidence that this is the definitive origin of the terms ‘Men of Kent’ and ‘Kentish Men’.

All a matter of social life?

A different theory is that the distinction between Men of Kent and Kentish Men is not about geography, but social history.

Writing in 1735, Reverend Samuel Pegge noted that there were several theories about the origin of the two phrases, but that “the current idea is that ‘a Man of Kent’ is a term of high honour, whilst ‘a Kentish man’ denotes but an ordinary person in comparison with the former.” Snobby!

But, Reverend Pegge added that he had read of other sources which defined men of west Kent as Men of Kent and those of east Kent as Kentish Men, which rather muddies the waters.

In the 1850s, discussions on the matter got rather catty. In 1852, several strongly worded letters – the Victorian equivalent of an internet flame war – were sent to the journal Notes and Queries after one correspondent posted this innocent question:

“Men of Kent and Kentish Men. The natives of Kent are often spoken of in these different terms. Will you be so good as to inform me what is the difference between these most undoubtedly distinctive people? B.M”

You can almost hear the sound of pens scribbling furiously as replies were written out. Some respondents argued the difference went right back to the Middle Ages, others than it was purely geographical. Some trotted out the Reverend Pegge’s idea about social class, others drew on ancient legends (more to come on that). Some people, including the editor of the journal, W.J. Thoms, suggested that Men of Kent were people who had lived in the county since the dawn of time, whereas ‘Kentish’ was for more recent interlopers (like Medway Geordies, perhaps…). It seems that the question was never actually settled, and I wonder whether poor old ‘B.M.’ ended up wishing they had never asked.

The Unconquered

Now, I don’t know about you, but I think the theories so far are lacking something. They’re perfectly fine, but none of them are completely persuasive. And they’re not very exciting, are they?

But there’s a much more interesting story about the origins of the term ‘Man of Kent’ that I really like. It’s a story about courage, standing your ground, and sticking up for you and yours. A tale that has inspired ballads, songs and monuments. It’s the legend of how the men of Kent faced down William the Conqueror after the Norman conquest of England.

The story goes that after the Normans landed at Dover, they were heading to London via Watling Street, which runs right through Kent. Near Swanscombe, they were ambushed by a large body of armed men from Kent. The men from Kent carried oak branches (to symbolize peace) and swords (which did not symbolize peace), and were led by Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Eghelsig, abbot of St Augustine’s monastery. The men stopped William in his tracks and gave him a stark and simple choice – peace with the people of Kent, or war.

Augustin Thierry wrote about the encounter in his book, The History of the Norman Conquest. According to Thierry, we don’t know exactly what happened that day – whether there was a battle or a treaty – but either way the Kent army promised to allow William to continue on one condition – that he let them remain “as free after the conquest as they had been before it.”

Thierry doesn’t think much of this, describing what happened as “deplorable capitulation.” But the Kent army was clearly pretty intimidating, as William and his men agreed to the terms and took a different route to London. The Kent army’s actions also meant that the county stayed relatively independent until the Middle Ages. It is believed that the meeting between the two sides is the origin of Kent’s motto, ‘Invicta’, which means ‘unconquered’.

Regardless of whether you see the armed men of Kent as giving in to the oppressor, or courageously trying to stick up for themselves against a massive invading army who had already defeated King Harold at Hastings, the encounter became the stuff of legend.

The Kentish Ballad, written about 1600 by Thomas Deloney, paints a heroic picture of the meeting:

“But when the Kentish-men had thus

The Kentish Ballad by Thomas Deloney

Enclos’d the conquerer round,

Most suddenly they drew their swords

And threw the boughs to ground;

Their banners they display’d in sight,

Their trumpets sound a charge,

Their rattling drums strike up alarms,

Their troops stretch out at large.

The conqueror, and all his train,

Were hereat sore aghast,

And most in peril, when they thought

All peril had been past.

Unto the Kentish men he sent,

The cause to understand,

For what intent, and for what cause,

They took this war in hand;

To whom they made this short reply,

For liberty we fight,

And to enjoy king Edward’s laws,

The which we hold our right.”

Another ballad, The Brave Men of Kent by Thomas D’Urfey, starts with two verses that put the incident in a glorious light.

“When Harrold was invaded

The Brave Men of Kent by Thomas D’Urfey

And falling lost his Crown;

And Norman William waded

Through Gore to pull him down:

When Countys round with fear profound,

To mend their sad Condition;

And Lands to save, base Homage gave,

Bold Kent made no submission.

CHORUS

Sing, sing in praise of Men of Kent;

So Loyal, brave and free;

‘Mongst Britain’s race, if one surpass,

A Man of Kent is he.

Now, some say that this story is not only where the phrase ‘Man of Kent’ comes from, but that it is also the source of rivalry because the Men of Kent allegedly stood up to William more bravely than the Kentish Men. Indeed, Reverend Samuel Pegge, writing in 1735, may have had this in mind when he said, “a Man of Kent is a term of high honour, while a Kentish Man denotes but an ordinary man.” Francis Grose, writing in 1790, uses the legend as the basis for the distinction, as does the (excellently named) Reverend Ebeneezer Brewer in his Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.

A very important BUT

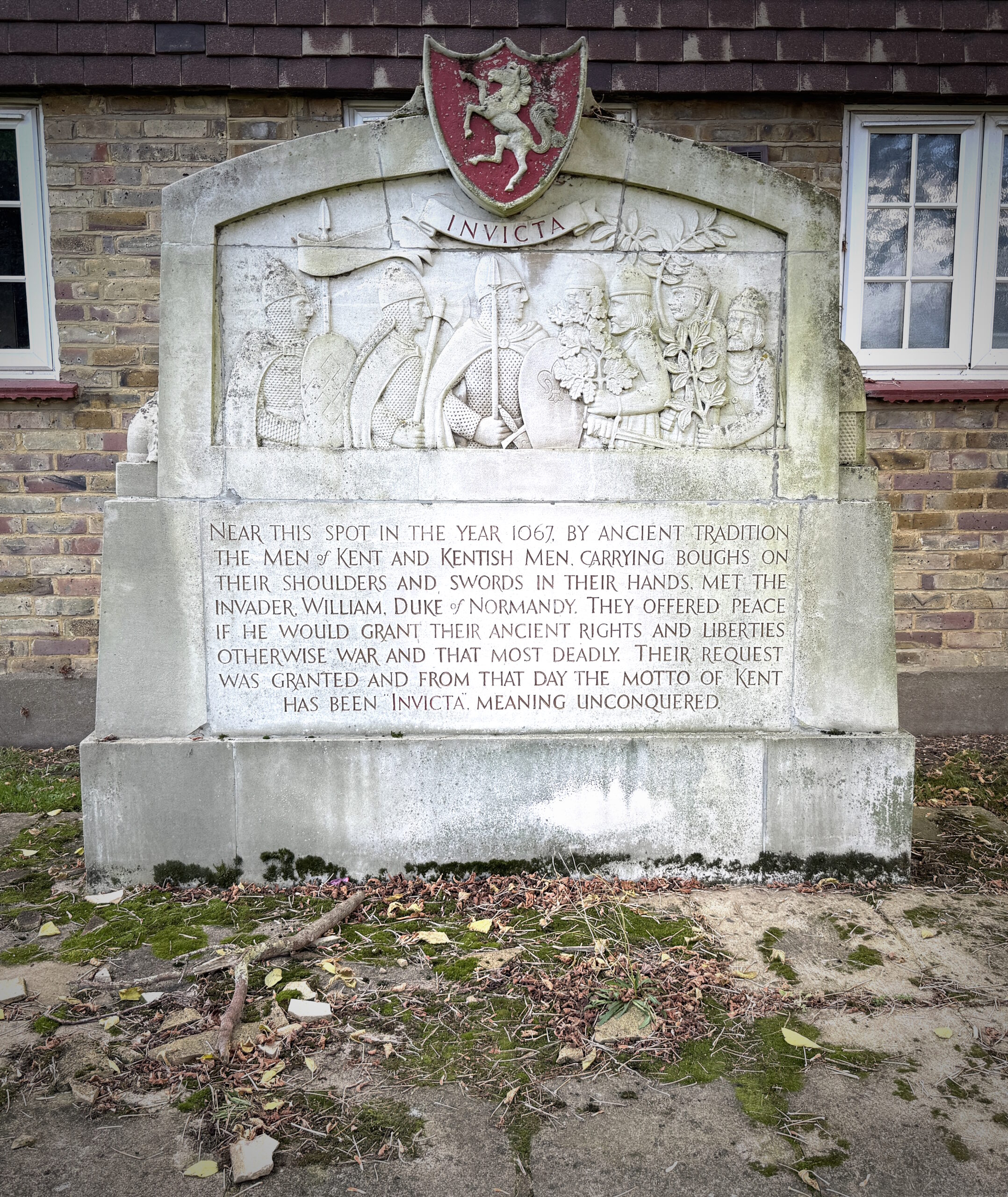

However, there is no evidence that those who met William’s army were exclusively Men of Kent or Kentish Men. The ballads above refer to both. Similarly, a monument erected in 1958 by the Association of Men of Kent and Kentish Men to mark the encounter heralds the bravery of both Kentish tribes:

The text on the stone reads:

Near this spot in the year 1067, by ancient tradition the Men of Kent and Kentish Men carrying boughs on their shoulders and swords in their hands, met the invader, William, Duke of Normandy. They offered peace if he would grant their ancient rights and liberties, otherwise war, and that most deadly. Their request was granted and from that day the motto of Kent has been “Invicta” meaning unconquered.

Text on the Swanscombe Monument

The monument originally stood on Watling Street, but was moved to the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul’s church in Swanscombe when the A2 dual carriageway was built. It was designed by Sidney Loweth and sculpted by Hilary Stratton FRBS. The BBC Archive has a great video of the monument being unveiled by the Lord Lieutenant of Kent, on 23 September 1958.

The sound quality on the video isn’t magnificent, so here’s a transcript:

“It is today as I say nearly a thousand years later, that we proudly remember that time and unveil this memorial to mindedness, that led by Stigend the Archbishop of Canterbury, cheered on by the abbot of St Augustin, with oak leaves over their heads and swords in their hands, the Men of Kent advanced up Watling Street to defend their ancient liberties [applause]. And so, with that in our minds, and in proud memory of our great forefathers, when they that day defied – but defied in a friendly and welcome spirit – the great duke William of Normandy, I now unveil this memorial to that historic occasion [applause].”

I’m sure those swords looked very ‘friendly and welcoming’…

Later in the video, talking to an interviewer – and presumably answering a question about why a decision had been made to raise a monument such a long time after the event – Lord Lieutenant Cornwallis goes on to say:

“Well I think because we were probably rather slack and idle about it, but the county society, the Association of Men of Kent and Kentish Men, have recently been trying to preserve our old legends and things, and they at council meeting decided they would commemorate it by erecting a monument on the site where the actual meeting with Duke William took place.”

I went to St Peter and St Paul’s church in Swanscombe to see the monument last weekend. I couldn’t help thinking that it looks pretty neglected and forgotten, in the corner of that little churchyard. Certainly it needs more publicity; my own Man of Kent had never heard about the Swanscombe legend, and had no idea this monument existed!

The verdict

So where does the phrase ‘Man of Kent’ really come from?

After all that reading and researching, all I can definitely say is that the origins of the phrase are disputed and lost in the mists of time.

The East or West of the River Medway distinction is nice and straightforward. It’s probably the explanation most people would use today.

The Swanscombe incident must have some truth in it to have inspired so many stories and ballads. Given my Man of Kent’s firm sense of fairness and justice (and how bloody stubborn he can be when he feels like it), I can certainly imagine him telling an invading Norman army to jog on back in the day. But, for the reasons mentioned earlier, this can’t be the origin of the term ‘Man of Kent’.

Many researchers on this subject have thrown in the towel. Reverend Pegge gave up and said, “The most probable solution of the matter is that the two are synonymous.” James Lloyd concluded his study on the subject by saying “A ‘Man of Kent’ and a ‘Kentish Man’ are exactly the same thing. The terms were originally interchangeable and their supposedly ancient distinction is a modern artifice.”

My own theory is that their defiance of William the Conqueror distinguished the people of Kent as a whole, and the terms ‘Man of Kent’ and ‘Kentish Man’ are nowadays mainly geographical distinctions. Regardless of whether you’re a Man or Maid of Kent, or a Kentish Man or Maid, you come from a county with a grand history that’s rich in legend. But one should endeavour not to mix up a Man of Kent with a Kentish Man, just to be on the safe side.

In the end, does it even matter?

I say yes.

A name like ‘Man of Kent’ or ‘Kentish Maid’, (or ‘Geordie’, or ‘Brummie’ or similar) isn’t just an affectionate nickname or historical quirk. It’s a distinction. An identifier. A link to the past and a signifier of the present. To say ‘I’m a Man of Kent’ is to say “I am from East of the Medway, and a part of those stout-hearted people who would not let themselves be conquered. I am proud to say it, and to say it in such a way that people ask me more, so that I can tell them more – tell them the stories, the history and legends. To keep these ideas and this place and these stories alive and to tell them to others, so that one day someone might say to a friend, ‘Did I tell you about that time I met a Man of Kent? Do you know why they are called Men of Kent? Well, let me tell you.’” And so, the history continues.

Further reading

- A Provincial Glossary with a collection of local proverbs and popular superstitions, Francis Grose (2nd edition) (c.1787)

- The History of the Conquest of England by the Normans, Vol.1, Augustin Thierry, translated by William Hazlitt (1847)

- Popular Music of the Olden Time by William Chappell (c.1850s)

- Notes and Queries, (Vol 5, No. 127), 3 April 1852

- Dr Pegge’s Alphabet of Kenticisms, and Collection of Proverbial Sayings used in Kent, W. Skeat (1874)

- The Kentish Garland, Julia Vayne and Joseph Ebbsworth (1881)

- Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E. Cobham Brewer (1894)

- Kenticisms

- The Kentish Demonym – or, the demonym of Kent, by James Lloyd

Leave a Reply